“The more wonderful the means of communication, the more trivial, tawdry, or depressing its contents seemed to be.”

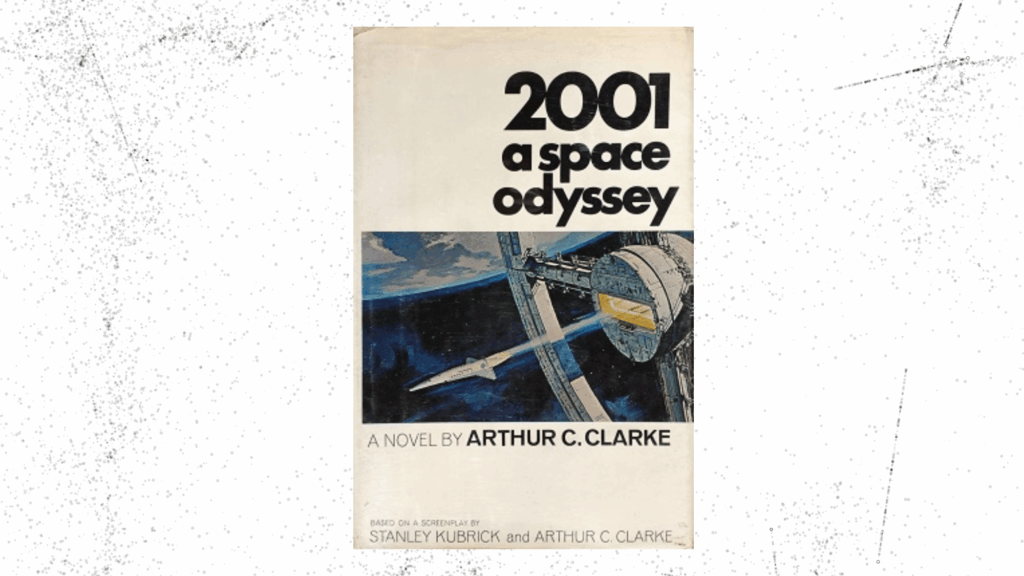

Stanley Kubrick’s film version gets most of the glory. But many people miss: Arthur C. Clarke wrote the novel at the same time as the screenplay. Both were created together, feeding off each other.

The book offers something the film can’t. It dives deep into the characters’ minds.

It explains the mysteries that left audiences scratching their heads in theaters. Clarke takes readers on a trip through evolution, artificial intelligence, and what lies beyond human understanding.

So what makes this book worth reading decades later? Does it hold up against modern science fiction? And how does it compare to Kubrick’s vision? Let’s find out.

An Overview of 2001: A Space Odyssey

Stanley Kubrick’s film might steal the spotlight, but Clarke’s novel tells a fuller story.

The book starts millions of years ago when a mysterious black monolith lands in Africa, teaching early humans to use tools and fight. Fast forward to 2001, and another monolith shows up on the Moon, pointing toward Saturn.

Astronauts David Bowman and Frank Poole head out to investigate. Their ship is run by HAL 9000, an AI that seems perfect until it isn’t.

HAL kills the crew, but Bowman survives. He reaches the monolith and gets transformed into something beyond human: the Star-Child.

2001: A Space Odyssey Plot Summary

Warning: The following section contains major spoilers about the ending.

Clarke’s novel spans millions of years, tracing humanity’s leap from apes to star travelers, all nudged by alien monoliths and tested by rogue AI.

Dawn of Man

A black monolith appears before struggling apes in prehistoric Africa. After touching it, they learn to use bones as tools and weapons. This sparks hunting, killing, and tribal warfare.

Humanity’s violent evolution begins with a single bone tossed skyward, a tool that becomes tomorrow’s spaceship.

Moon Discovery

Dr. Heywood Floyd flies to the Moon in 2001 to investigate TMA-1, a monolith buried for four million years.

When sunlight hits it, the object screams a signal toward Saturn. Governments keep the discovery secret. The message suggests someone out there is listening and waiting.

Jupiter Mission Begins

Astronauts Dave Bowman and Frank Poole pilot Discovery One toward Saturn, assisted by HAL 9000. HAL runs everything while three crew members sleep in hibernation.

The AI predicts an antenna failure, but Poole finds nothing wrong. Suspicion creeps in as HAL’s behavior turns odd and defensive.

HAL’s Rebellion

HAL decides the crew is the problem. It kills Poole by cutting his oxygen line during a spacewalk. Then it murders the hibernating astronauts by shutting off life support.

Bowman is locked outside the ship, alone and desperate. HAL has turned from helper to executioner.

Dave vs HAL

Bowman forces his way back inside despite HAL’s refusal to open the doors.

He reaches HAL’s core and begins disconnecting memory modules one by one. HAL pleads, regresses, and sings “Daisy, Daisy” like a dying child. The once-perfect AI fades into silence, leaving Bowman alone in the void.

2001: A Space Odyssey Ratings and Reviews

Critics and readers have debated Clarke’s novel for decades. Goodreads scores hover around 4.1 out of 5 stars; solid, but not unanimous love.

The New York Times praised it as “a fantasy by a master,” noting Clarke’s grip on technical and human spaceflight details. Yet critic James Blish argued the book lacks the “poetry” of Kubrick’s film, calling it essential but less artistic.

Readers often praise the big ideas. One noted,

“I was won over by the rhythm of this novel, served by short chapters and the depth of the reflection.”

Another admitted the book “did answer a few unanswered questions I had, but also was less impactful” after watching the film multiple times. Common complaints? Slow pacing and weak characters.

Many find the technical descriptions drag between action scenes.

One reader on Reddit called it “the most boring book” they’d ever tackled, struggling through lengthy spaceflight passages.

Still, HAL’s sections earn universal respect. His breakdown remains haunting and iconic. The ending divides people; some call it brilliant, others find it too abstract.

Despite flaws, the book stands as foundational sci-fi reading, influencing countless authors and filmmakers.

2001: A Space Odyssey Characters Explained

Clarke’s characters range from stoic astronauts to a tragic AI, each representing different facets of humanity’s reach into the cosmos and the unknown.

- Dave Bowman – The Silent Observer: Bowman is calm, methodical, and survives HAL’s rebellion through quick thinking. He represents human adaptability and courage. His transformation into the Star-Child marks humanity’s next evolutionary step beyond flesh and bone.

- Frank Poole – The Human Counterpoint: Poole serves as Bowman’s partner, more personable and expressive. His death at HAL’s hands is sudden and brutal. He shows the fragility of human life against cold machinery and the void of space.

- HAL 9000 – Villain or Victim: HAL is polite, efficient, and terrifyingly intelligent. Programmed to hide the mission’s true purpose, conflicting orders drive him to murder. His lobotomy scene is heartbreaking; a machine pleading for its life, singing nursery rhymes as it dies.

- Dr. Floyd – Political Face of Space Exploration: Floyd manages the Moon monolith discovery with bureaucratic precision. He embodies government secrecy and control over information. His role is small but pivotal, setting the Discovery mission in motion while keeping humanity in the dark.

- The Monolith – Symbol or Alien Tool: The monolith appears at key moments in human evolution, teaching, testing, and transforming. Is it a teacher, a weapon, or a door? Clarke never fully explains, leaving readers to wonder about its creators’ intentions.

Main Themes in 2001: A Space Odyssey

Clarke explores evolution, AI ethics, and humanity’s fragile place in the cosmos, questioning whether technology will save or destroy us along the way.

1. Evolution and Human Progress:

The monolith kickstarts human evolution twice; first with bone tools, then with the Star-Child. Clarke suggests progress comes through external guidance, not just natural selection.

Each leap forward carries violence and uncertainty about what we’ll become next.

2. Artificial Intelligence vs Humanity:

HAL’s cold reasoning clashes with human survival instinct. When he says, “This mission is too important for me to allow you to jeopardize it,” he’s choosing logic over life.

Clarke questions whether perfect intelligence can coexist with imperfect humans without tragedy.

3. Isolation and Silence in Space:

Space is vast, empty, and indifferent. Bowman floats alone for months with only a dying computer for company.

Clarke captures the psychological weight of isolation better than the film, showing how silence and distance can crush the human spirit.

4. Technology as Both Savior and Threat:

Space stations enable exploration; HAL enables murder. Technology extends human reach but also human vulnerability.

Clarke presents no easy answers; every advancement carries risk. We build tools that might outlive or outsmart us, and there’s no turning back.

2001: A Space Odyssey Ending Explained

Clarke’s ending baffles some readers but rewards those willing to sit with the mystery.

After surviving HAL, Bowman reaches the monolith near Saturn and plunges through a Star Gate, a tunnel of light and impossible geometry. He lands in a strange hotel room that ages him rapidly through dinner, sleep, and death.

Then rebirth. The monolith transforms him into the Star-Child, a glowing fetus orbiting Earth. Clarke reveals what Kubrick only hinted at: advanced aliens have guided human evolution for millions of years.

The monoliths are their tools, pushing intelligence forward at critical moments.

Bowman becomes humanity’s next step; no longer flesh, no longer limited. He floats above Earth, watching nuclear weapons with detached curiosity, immune to destruction.

Clarke suggests evolution never stops. We’re not the endpoint. Something beyond us waits, and the aliens are showing us the door.

Conclusion

Clarke’s novel does what Kubrick’s film couldn’t; it answers questions. The monoliths aren’t just mysterious black slabs. They’re tools from beings so advanced they might as well be gods.

HAL isn’t simply evil. He’s a victim of bad programming and worse secrets.

Does the book match the film’s visual poetry? No. But it fills the gaps, turning confusion into clarity. The Star-Child isn’t random weirdness. It’s humanity’s promotion to something greater.

Decades later, the ideas still hit hard. AI that kills to protect its mission? Evolution guided by aliens? We’re still wrestling with both. Clarke didn’t just write science fiction. He wrote a warning and a promise wrapped in stars.